ALLONS, ENFANTS DE LA PATRIE…

"40 Stories About Famous Composers" by Dragan Tenev - Rouget de Lisle, May 1760 – June 1836

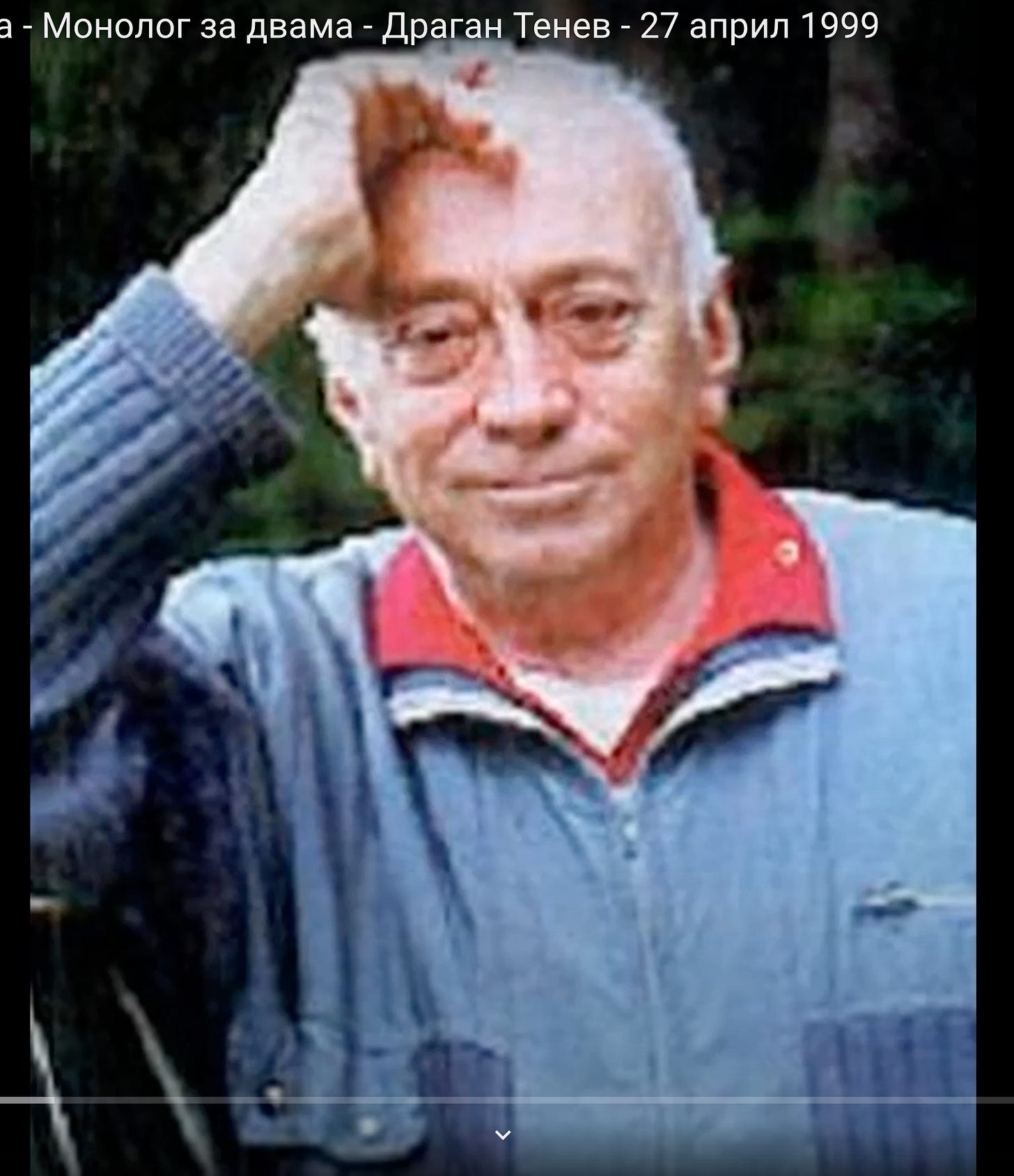

Preface: “Happy Birthday, dear Dragan Tenev.”

Dragan Tenev, April 12, 1919, Shumen - September 27, 1999, Sofia, Bulgaria.

The author of the short stories about great painters and composers posted here in translation from Bulgarian, Dragan Tenev, was born in Shumen, Bulgaria on April 12th, 1919. In 2025, this is Lazarus Saturday, when Orthodox Bulgarian Christians celebrate that “Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead, because he is the King of the living”. Coincidentally, the last photo of Tenev is also from April, taken on 27th of April 1999 during an interview, shortly after his 80th birthday. He passed away on 27th of September that same year. Besides being a great art historian, he was an officer, a multilingual lawyer, a writer, a journalist, and a dancer. Strange enough, after his death, his ashes were never found. May be Jesus raised him from the dead?

As it happens, his story about the French composer Rouget de Lisle comes directly after his lovely story about Mozart and, as it happens, La Marseillaise was written shortly after “the Legislative Assembly in Paris declared war on Austria and Prussia on April 25th, 1792”, i.e. four months after the early passing of the brilliant German composer in Vienna. What a stark contrast between the shining beauty of the young German’s music and the raw French Freemason Jacobin Terror roar. de Lisle didn’t even use a metaphor, he and his comrades were, literally, cutting throats:

“Arise, children of the Fatherland, The day of glory has arrived! Against us, of tyranny the blood-stained standard is raised. Do you hear in the countryside, those blood-thirsty soldiers ablare? They're coming right into your arms to tear the throats of your sons, your wives!”

And, what a sad irony: the French anti-royalists immediately installed themselves on thrones once they had manipulated and slaughtered their co-citizens, including children. Napoleon’s General Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte was installed by force as the King of Sweden, after the brutal assassination of the great Swedish King Gustav III in March that same 1792 and after that later forced exile of his heir. Bernadotte and his wife from Marseille never even learned Swedish. That French “line” of the common from southwestern France is still on the throne in Sweden.

And yet, in the long run, Mozart and his “A Little Night Music" won the hearts of the future generations world wide.

ALLONS, ENFANTS DE LA PATRIE…

On April 25, 1792, news arrived in Strasbourg that stirred the entire city: the Legislative Assembly in Paris had declared war on Austria and Prussia.

The enthusiasm that erupted among the citizens was like a storm. Men, youths, old folks—even the women—all rose as one. They were ready to fight to the last drop of blood to defend the revolution and repel the invaders who sought to restore the old, hated order of the masters in France.

The tricolor flag waved above all houses.

To mark this great event, the city’s new mayor, Citizen Dietrich, decided to host a reception at the town hall for those who would soon depart for their regiments to defend the endangered fatherland. He immediately set about fulfilling this intention, and the very next evening, the windows of the grand hall in the municipal building shone brightly, solemnly lit.

The reception was going splendidly. When the guests’ spirits were sufficiently lifted and they had reached the bottles of fizzy champagne, one of them struck up a patriotic song that was in vogue at the time. Everyone present joined in, and the hall thundered with their voices.

“This one’s just like the others coming from Paris!” Dietrich said to the general standing to his left, who was eagerly devouring a large piece of cake. “I can’t believe that such a song would inspire soldiers heading to the battlefield.”

“There’s some truth in what you say, Mr. Mayor,” the general replied, “but until we have something better, we’ll sing what we’ve got. Besides, listen—it’s not as bad as you think.”

To prove his point, the general began humming along, though it was clear he didn’t know the lyrics.

Dietrich listened again. Suddenly, an idea struck him:

“What if I announce a contest for a march for the Rhine Army? Couldn’t something better come of it?”

He scanned the room, and his eyes happened to fall on the unassuming pioneer captain, Rouget de Lisle. The mayor reconsidered his plan.

“This fellow plays the violin well and writes bad poetry. Instead of a contest, I’ll ask him to compose a march. Let him try. Who knows—something decent, maybe even good, might come of it. Miracles happen sometimes!”

Dietrich signalled the captain to come closer.

“Dear de Lisle,” he said warmly, placing a hand on his shoulder, “I have a special request for you. You understand the language of the muses, and Orpheus’s songs are no mystery to you. Promise me you’ll soon try to write a fine patriotic song. Our Rhine Army is ragged and underfed, but I’d love for it to have something that outshines all other armies—a wonderful song to lead it into battle. Listen to what they’re singing now. Can you call that good?”

De Lisle halfheartedly promised to try, unable to refuse outright, but as soon as he rejoined his friends, he forgot all about it.

He only remembered his promise when he was already on the street, heading home. The night was quiet. The spring sky glimmered silver above him, dotted here and there with small white clouds. At the end of the empty street loomed the majestic, enormous silhouette of the cathedral and the black rooftops of sleeping Alsatian houses, bathed in pale moonlight. Peace and calm reigned.

“And all this will vanish in an instant if the enemy comes here!” de Lisle thought involuntarily, quickening his pace without realizing it. He reached home almost at a run, grabbed his violin, and tuned it quickly. He ran his fingers over the strings and picked up the bow. Whether it was the excitement and emotion of the day or perhaps the glasses of champagne he’d drunk—captain de Lisle couldn’t tell—but the very first measures he drew from the strings pleased him. He immediately took a squeaky quill and jotted them down on a sheet of music paper. Then he kept playing. Before his eyes, landscapes of rivers and plains, mountains and valleys flashed by at a dizzying speed. This was his homeland—France of the French, not the France of the hated king. The storm of uprising towns and villages roared in his ears. He heard Paris thundering with cannon fire—he saw its barricades. And as he translated these visions into tones, the words seemed to come on their own. He wrote them down with a trembling hand and then spoke them aloud, clear and sharp:

“How beautiful it is!” he thought, satisfied, and continued working feverishly, seized by a strange inspiration he’d never felt before.

When he finished the song, the timid light of morning was already creeping into his modest little room. Then, utterly exhausted, de Lisle threw himself onto the bed, still in his uniform, and fell into a deep sleep.

He opened his eyes only at two in the afternoon. He quickly gathered the sheets scattered across the floor and, paying no attention to his crumpled uniform, ran to Dietrich.

“Mr. Mayor, Mr. Mayor, the march is ready! If you’ll allow me, I’ll play it for you right now!”

Stunned by the speed with which the captain had fulfilled his request, Dietrich was captivated by the melody and the lyrics. There was something powerful and compelling in them, something no one could resist.

The mayor’s delight knew no bounds. He took the sheet music from the captain’s hands and sat at the clavichord himself. After playing the song once, he began to sing, and de Lisle joined him. The march sounded magnificent.

“There’ll be a fine surprise tonight!” Dietrich said, thrilled, and immediately sent for his wife.

“Citizen,” he said with a smile and a bow as she entered the room, “I humbly ask you to invite last night’s guests back for dinner tonight. I’m preparing a big surprise for them and counting on your help, yes?”

That evening, the guests once again took their old seats around the table. When dinner ended, they were so eager to see what would happen that they shouted in unison:

“The surprise! The surprise!”

“A little more patience, dear friends!” Dietrich calmed them, ordering champagne to be brought. Then he stood, approached his niece, and with a ceremonial bow, said:

“Now, Renée, I trust you won’t refuse to sit at the clavichord and play our guests the awaited surprise.”

Dietrich offered his hand to the girl and led her to the small stool. Everyone gathered around with full glasses in hand. Renée glanced at them for a moment, then struck the keys boldly and confidently. The first measures of the melody rang out, solemn and captivating. Dietrich and de Lisle sang together: Allons, enfants de la patrie…

A spark seemed to sweep through the room. The song sounded spirited. Its notes flew out the open window, mingling with the warm April breeze outside, which carried them to the four corners of revolutionary France.

A few months later, a battalion of five hundred Marseilles set out from Marseille toward the Rhine. They marched to die for freedom. All along the road to Paris, the Marseilles sang the “Rhine March” without cease. People in the villages and towns they passed cheered with enthusiasm:

“Listen, listen to how beautifully these Marseilles sing!”

“The song of the Marseilles! The song of the Marseilles!”

They reached Paris. Some nameless citizen of the revolution dubbed their song “La Marseillaise,” and that name stuck forever.

Allons, enfants de la patrie…—thousands of Frenchmen sang under the waving tricolor flag, falling in the fight for freedom. The song faded on their dead lips, but others took it up at once, and it traveled from barricade to barricade.

No one remembered anymore who had written it, who had created it. And what did the author matter to them? Whoever he was, his song belonged to everyone—to the entire people.

Many years later, when the modest captain Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle sat by the lit fireplace in his home in the evenings, he loved to recall his youth. And whenever he remembered that distant April night in 1792, the white-haired old man knew that what had beaten in his chest then was not his own heart, but the vast, great heart of the French people, who had taken up arms in those heroic days to defend fraternity, equality, and liberty…

Note: ALLONS, ENFANTS DE LA PATRIE - COME ON, CHILDREN OF THE FATHERLAND…