THE LAST ONE

"Small Stories About Great Artists" by Dragan Tenev, 1981. - Oscar-Claude Monet 1840–1926

Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral. West Facade Sun Light. 1894. Oil on Canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Preface: Since January 1st of 2023 we took a stroll together, through time, in Europe, starting with 1400s Renaissance and, now, for the first time, we step into the 1900s of fine arts. There is a big change. All of a sudden we see the same painting title, by one artist, Claude Monet, in many museums. His “Rouen Cathedral” hangs on the walls of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the National Museum in Serbia, and number of others. All at the same time! How is that possible? The secret is that Monet painted and exhibited series of the same object depicted in different sunlight and from different viewpoints. Rouen Cathedral at sunrise, Rouen Cathedral at sunset, Rouen Cathedral in midday sunlight... None of them is identical to the other but they all represent and are called the same: “Rouen Cathedral”. Similarly with lily lakes, flower gardens, the St. Lazare train station, and so on. I posted here two paintings chosen by Tenev himself, reproduced in his original book (not the self-portrait).

Of course, Botticelli, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Giorgione, Rafael, Tintoretto, Dürer, Holbein, Bruegel, El Greco, Velázquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, Hals, Rembrandt, Gainsborough, Goya, Delacroix, (not sure about Daumier), and Millet must have known that as the light changes so does their painting. May be they did paint series in different sunlight but never exhibited it. They painted their interpretation of the perfect Platonic idea, untouched by time. It took centuries before a painter dared to exhibit the same very object in different light of the day, i.e. to exhibit the impossibility of catching completeness without abstraction.

I can understand Monet. From my house, in the countryside, I see both sunrise and sunset over the same lake next to the same forest. Yet each and every moment of each and every day the picture infront of me changes, the lights and shadows swiftly move and the colour view is never the same. Sometimes, the lake is a blank mirror reflecting, perfectly, the crowded trees, the cloud fleets, the long-neck geese. At other times - rough and tough, as if it is the end of time. All in the same day. Often, I want to stop the world and admire an especially immortal impression of light in colour touching the lake and the bird wings, only to find it impossible. Monet felt the same; he said so.

Tenev’s story is not about that. Who would have thought that “the last Mohican” of Impressionism, who dedicated his life to painting water lilies, cathedrals and train stations bathing in sunlight and steam, was a brave patriotic soldier and almost lost his life at war.

THE LAST ONE

Giverny, December 8, 1926...

At the front of the cart, stiffened by rough pine boards, was a boy in a leather hat. He was carrying the cross. On the black-painted elliptical tin attached to it was written in plain bronze paint: "Oscar-Claude Monet — Paris, 14. XI. 1840/ Giverny, 6. XII. 1926".

Nothing else. It was the last will of Monet himself to be buried as a simple peasant.

Behind the little boy wearing his white ritual robes over the winter coat, which had began to fade, paced the parish priest, dragging his right leg slightly - a memory from the battles at the Marne, when he had performed his Christian duties near a dying soldier. Behind the priest, the horses dragged the cart, and behind the cart, with his hat down, stood a short, chubby old man, dressed in an expensive but hopelessly old-fashioned coat. It was Georges Clemenceau - "The Tiger," who had waited nearly fifty years to repay the Prussians for France's defamed honour in 1870.

Then came the relatives, the officials and the fans. Among them was a young officer dressed in the uniform of colonial cavalryman from Algeria. A wide mourning was attached to the sleeve of his overcoat.

- Who is this "African"? - someone asked.

- I have never seen him before, - the questioner replied.

The only one who knew the officer was the old gardener per Jérôme. He also followed his master's coffin to the cemetery at Giverny.

In an instant, the eyes of the cavalryman and per Jerome met. The officer approached him and took him by the arm.

- You remember me, don't you? - the cavalryman asked.

- Indeed, I remember you, - replied the old gardener. - You came to Mr. Monet last year.

The officer shook his hand like an old friend and the two continued side by side, each in their thoughts.

"The happy times flew irrevocably away..." the old gardener repeated to himself, constantly rewinding the morns of the past, when from five o'clock in the morning Monet stood by the artificial lake in the park of the villa and watched for hours the water lilies, while the officer present next to the gardener could not banish from his consciousness the only encounter he had with the great artist. It was a beautiful September day, sunken in the sun. Captain Maurice de Champign had found himself at Giverny around ten o'clock in the morning and had asked to inform that he was coming from Africa and wished to meet him, but only on the condition that this meeting would not hamper the old artist's daily regimen.

Monet had gladly accepted it. On that autumn morning he felt very lonely, as if forgotten by everybody. A foreign voice would, probably, help him get out of his oppressive thoughts. At the same time, the officer who asked to be admitted came from Algeria. He served in the same regiment in which Monet himself had served more than sixty years ago. Military service leaves deep traces in the hearts of men and they forget them only in the grave. The old painter went to the hall where the officer was waiting. When he entered the spacious reception room, the guest got up, strаightened and respectfully said:

- Captain Maurice de Champign. Thank you for deigning to receive me, Mr. Monet!

- Good afternoon, Captain! - he oriented himself rather by his voice, as the eighty-five-year-old artist, who was now almost completely blind, could only distinguish silhouettes. - Here you go, sit down, please.

- After allowing me to help you first, my dear Monet, - replied the Captain of the cavalry, taking the old man's hand. - Where would you prefer?

- I'm indifferent, my boy, - Monet smiled sadly. - I used to like to sit in the armchair by the big window, but now . . . It doesn't matter where I sit.

The captain led the old painter to the large armchair by the wide French window and helped him sit in it.

- Thank you, Mr. Captain, - the artist rested his thin dry hands on the back of the armchair, and Captain de Champign thought: “So these are the hands that created the paintings I love so much”.

- I am very grateful that you have deigned to receive me, my dear Monet, - said the cavalry officer, who was still standing by the artist's chair. - It is a real pleasure for me to see you in person, having admired your painting so much.

- Are you interested in painting? - The old man wondered.

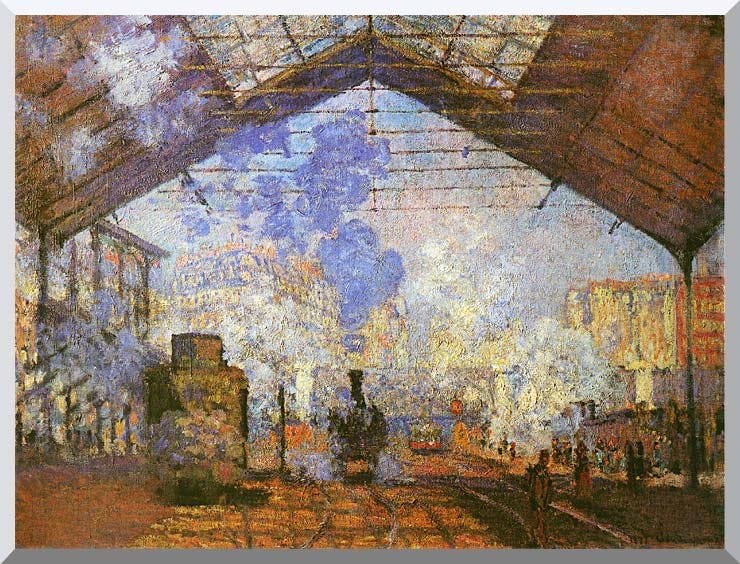

Claude Monet, Gare Saint-Lazare. 1894. Oil on Canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

- I must confess to you, yes, dear Mr. Monet, - replied the officer. — But let me convey to you first of all the fervent greetings of my comrades from Algeria, who wish you, on the occasion of your anniversary, good health.

The Captain relaxed in the armchair opposite the artist and added:

- When the officers of the regiment learned that I was coming to Paris for a six-month course at Saint-Cyr, they shouted in chorus: "Maurice, Maurice, you must visit our brother, Monet. He served in the second squadron under Captain Escolier, whose portrait hangs on the wall of the regiment's headquarters”.

- Does the portrait of Captain Escolier still exist? - The old man asked excitedly.

- Of course, Mr. Monet! In the regiment they keep it as a relic. The people of the Algerian cavalry never forget that you served in it, that you wore the same uniform as we do, - Captain de Champign assured him.

- Nice to hear this, Mr. Captain, - said the old artist excitedly. - Now that I can no longer work and live in solitude, the memories of my military service in Africa often visit me.

Monet took a short pause.

- It's scary to experience so many people and end up alone, - he added. - Georges is the only living of my oldest comrades. Everyone else is dead.

- Excuse me, Monet, who is Georges? - The captain asked. He didn't know an artist with that name.

- Georges is not an artist, my boy. This is Clemenceau. But to me, who knew him sixty years ago, he remains Georges. - A smile ran on the lips of the 'ideologue' of the Impressionists. - You know, he pulled out of my hands, almost by force, the second of the last two self-portraits I had painted. He pulled it out because he claimed that I would destroy it as I had destroyed the first. When I pushed him into the car, I wanted him to look at it with my eyes! - Monet laughed cheerfully for the first time. - He deserved that revenge, didn't he? You have no idea what a stubborn man he is when he thinks of something!

- I think I have, Mr. Monet, - replied the Captain in the same tone. - I took part in the war.

A shadow passed over the face of the old artist.

- In this war, they killed my son by Camilla, - he said in a changed voice. - I couldn't keep it in the back of my head. Sam wanted to be assigned to a combat unit.

The two men were silent and then Monet said:

- All the Monets always ended up on the side of France when she needed our help. Always.

- I know the history of your life, Monet, - said Captain de Champign. - I am familiar with your participation in the war in the seventieth year. And I must add — your courage in Algeria is still remembered. It is still an example for the fighters.

- Algeria and the desert made me a real man, my boy, - said Monet, regaining his excitement. - But I owe Africa a lot as an artist. The two fascinating years I had in Algeria, before the swamp fever brought me down, were of inestimable benefit to me. There, I was constantly seeing new things, and in my free minutes, I tried to reproduce what I had seen. You cannot imagine even how much I enriched my knowledge and how much my eyes benefited from it. At first I couldn't realise it. The impressions of the light and colours, which I received there were determined only later, and it was in them that the grain of my future quests was laid. - Monet paused for a moment and continued:

- In my day, one in seven young people was taken as a recruit to Africa: the one who drew the lot with the inscription "Africa". I drew that lot. My father, who did not want me to become an artist in any way, but insisted on making me a grocer like himself, offered to redeem me from military service, if I obeyed his will, but I had, already, chosen my path and did not retreat from it. I went to Africa. If I hadn't been ill, I would have served my entire seven-year service.

- I am convinced! - Captain de Champign smiled. - The enthusiasm in your voice was so sincere.

He stood up and asked:

- Don't I bother you already?

- On the contrary, my boy, - Monet said kindly. - On the contrary. I'm glad we're talking about things from so long ago. Can you allow me a vain question?

- Of course, Mr. Monet! - The officer smiled heartily.

- Which of my canvases have you seen and which ones do you prefer? - Monet asked, with some shyness in his voice.

De Champign listed many of his paintings from different periods. He seemed to know the Impressionist art well, spoke with understanding of it, drew parallels, compared, his assessments—this made a strong impression on Monet—were truthful and quite accurate. And, the Captain knew many details of both his life and the lives of his old companions, Manet, Sisley, Pissarro, Degas, and the other younger ones. He knew, not badly, the work of Gauguin and Van Gogh, but his preference was for Impressionist painting.

- Don't you find that, lately, my art has become a bit of an end in itself? - The old man was curious.

- Perhaps there is something like that, Mr. Monet, - the gentleman admitted delicately. - There is, indeed, something in your canvases after seventy that resembles virtuoso playing scales, but I have no right to judge it.

He was clearly hampered to be completely sincere and added:

- After all, I'm just an amateur. . .

- And perhaps that is your strength, - Monet said unexpectedly. - You are out of the game and have the perspective of the outside observer, while I was "inside" things and to some extent got carried away, but later I realised this, so that I could fight it myself. And, now it's over. I'm blind, I can't work, and believe me, I have no more incentives to live.

He paused a long time and added:

- Yes, Mr. Captain, this is the end.

"Or perhaps the beginning, Mr. Monet!" thought the Captain, and felt the icy wind pierce him. That eighth of December, when the "last of Mohican" of Impressionism was buried, was really cold.

Another brilliantly written story as brilliant as Claude Monet’s paintings. Written in a way that gives the reader the beauty of two dimensions within the same story. Much the way Monet paints two or more of the same object at different light. These stories really ‘make my day’. Too often we get caught up in the politics of the world; especially, in our own country’s politico, almost like an addiction. With these stories, I wean myself away from that addiction of damaging political gossip and cleanse my mind and soul with longing and renewal of enlightenment. How rich of a lovely soul the writer must be within herself to present to the reader an enchanting story. I love her for her imaginative writing as I love Monet’s painting. Trust in good writing and it will win you over every time and have you coming back without fail.

Sid Caradine

Columbus, Mississippi