SATIRIST WITHOUT A GRAVE OR A LETTER TO VLADIK FROM BRUSSELS

"Small Stories About Great Artists" by Dragan Tenev, 1981 - Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1525–1530 – 1569

Preface: Imagine, Sandro Botticelli was born and lived almost at the same time as Hieronymus Bosch! One can’t design a stronger contrast in art than this. Bright elegance and Venus beauty vs. dark sadistic hell. Yet, both are considered to be Renaissance artists. The original Renaissance in Florence, where it was born like a Greek goddess from the sparkling sea, had a mission, a specific purpose and inspiration, namely, the rebirth of Platonism. It was part of the abstract and grand philosophical project of the Medici, who brought even ballet as an art form to the world. The Northern Renaissance, associated with Bosch and Bruegel the Elder, had no such inspiration nor such goal. Nothing is graceful about their multiple figures. This contrast between the Italian light & grace and the Dutch roughness & scourge, could be a result of climate differences, because there were, of course, fights, cruelty and death in Italy too, yet they were not in the spotlight of the artistic attention in the south and if they were, they were painted in a glorious way, not as ugly grotesque terror. It is not surprising, then, that Bruegel the Elder, born shortly after Bosch’s death, is influenced by his landsman (Bosch was born in Hertogenbosch, close to a village called Bruegel) rather than by the Florentine masters, although he did visit Italy. However, although opposite in expression, the Southern and the Northern Renaissance, had one common trait, namely, humanism, the view that man can sculpt his own destiny, that he is not helpless in the mercy of God.

Dragan Tenev likes Bruegel the Elder a lot and calls him “my favourite”. May be he exaggerates the story about Charles V of Spain and his cruelty against the revolting Ghent because he reflects the sentiment in Bruegel’s art rather than what is reported as historic facts. Charles V was born in Ghent and the Low Lands were economically and socially privileged. Historians tell us that when he raised taxes, they revolted, but he didn’t “massacre 1/3 of the population”. He did, however, end the revolt and humiliate the participants on the streets. In that sense, artists are not historians nor reporters; they belong to the realm of fiction and emotional appeal, even when they try as hard as they can to “sound” realistic.

With this preface, starts the translation of Dragan Tenev’s small belletristic story about the great Bruegel the Elder. I am grateful to my friend Daniel who ably helps me to get edited digital versions of Tenev’s texts in Bulgarian with which I can work on the English translation.

Dear Vladik,

This time I'm calling you from Brussels. Suddenly, I was sent as a bullet to fix a mess, again. What can one do? When you are a legal adviser in foreign trade, you have no choice. You are ordered – you go. That's the game. For me, however, it turned out to be pleasant. Thanks to that game, I travel a lot, and this, I think, is great. Brussels is beautiful, no doubt about it. I'm sending you some postcards with panoramas, without describing its monuments. You are a smart boy and you will appreciate the beauty of the lush Flemish Baroque. The city, at least externally, is boring and does not look like Paris. It even seems to me that it radiates some provincial notes, despite its magnificently lit windows and colourful neon commercials. Of course, there are many museums, many churches and a lot of things to watch, but cinemas are expensive. Theatres and nightclubs are inaccessible to people like me. Fortunately, I was able to get the job done relatively quickly and I have three free days left. I shamelessly "stole" them, although I could take the plane back to Sofia a day earlier. Twenty-two percent of these three days — we have a tendency, lately, to express everything in percentages — I used this morning to look at the old Brussels cemeteries. By the way, you know that cemeteries in foreign cities have always been one of the "sites" that I visit most regularly. Even the Romans said, "Memento mori!"* and, as you can see, I make efforts in this regard. You will ask me what I was most interested in this time. Well, I answer at once: I was looking for the grave of one of my favourite artists, the Dutch master Pieter Bruegel. In fact, I'm not sure if I'm spelling his name quite correctly, because in the flemish mouth it sounds somewhat different, but unfortunately our phonetically rich alphabet lacks some muffled sounds. By the way, I am confident that they are achievable as a pronunciation only for the Flemings themselves. Anyway, that's not the point! What is more interesting is that I couldn't find my hero's grave, even though I made every effort in good faith. Neither in the cemetery management, nor in the church itself, they could give me any coordinates. The Belgians even assumed that such a tomb had never existed. And, I have to tell you, their old papers are perfect. They do not destroy anything and keep every paperwork associated with life and death for centuries! I asked them provocatively why they were kept for so long, and an old archivist said to me smilingly: "For cases like yours, dear Sir!" I left the cemetery by foot, and after all, as I walked along the way, I thought, resignedly, that Bruegel was not the only man of genius in the world whose grave was unknown. Can anyone please specify, for example, where Mozart's grave is? As you can see, the music of the genius composer continues to sound around us, and I think it will do so long after us as long as there are people in this world. The case of Master Pieter is similar. His paintings are around us! And, they still bring to us the fragrance of the heroic times in which he lived and worked, when the masses of his old Netherlands rose up in rebellion against their Spanish oppressors and fell worthy of the freedom of their native land, on whose fallow land they were born, lived and died. I know what you're going to say — “this weirdo of mine is writing me a letter about Bruegel instead of telling me some spicy Brussels story”. I have to assure you that you are not wrong! Yes, I'm writing you a letter about Master Pieter Bruegel—the Elder. And, I would add—about the great Pieter Bruegel, who, I think, have been envied by many young and old artists of all times. By the way, I will tell you that I saw for the first time in my life his original painting more than forty years ago. In 1936. Believe me, despite my youth at that time, the art of this devil amazed me! Without being able to explain to you why and how, I knew at once that I was in front of a picture painted by a brilliant hand. And this, remember, happened in Naples. In Italy, where I was surrounded by hundreds of masterpieces not only of Antiquity, but also of Quattrocento and the Renaissance, and by a bunch of other brilliant works of more recent times. Which of Bruegel's painting was in the Neapolitan Museum? I'll tell you —it was called “Parable of the Blind”. It was one of his last paintings. Perhaps one of the finest paintings painted in the entire sixteenth century!

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Parable of the Blind, 1568. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

Six blind men walking along a small village with sticks in their hands, holding each other "in a queue". The first blind man had already fallen into a hole. The second after him was presented at the moment when he lost his balance, and the other four, who felt the danger, had stopped. The painting made a very strong impression on me and made me look at the "sugared" images of the Italian masters around me with different eyes. I was, in fact, shocked. How this huge Bruegel painting had landed in Naples I do not know to this day, but since then, in all the museums between Madrid and Leningrad, wherever I landed, I have been constantly looking for works by this master, and as often as I discovered them, I have stood before them for hours. I couldn't break away. Today, I know that his best works are in Vienna, but there are things in the Prado that are worth seeing, not to mention places like Dahlem, Leningrad, etc.

Not a single author who dealt with Bruegel indicates the birthplace of the artist. Recently, however, I have been reading a very new English book about Bruegel's life, and its author claimed that my favourite was born in a village of Bruegel, where his name came from. According to him, it was located near the Dutch city of Hertogenbosch. That's a sonorous name, isn't it? I rolled up my sleeves and searched for this Hertogenbosch for a long time on the old map of the Netherlands. It turned out to be quite far from Anvers! But is all that the Englishman says true? At least for now, there are no documents to certify the place and year of the birth of Master Bruegel! Then what? Then I will use the words of the great modern Turkish poet Ecevit, who, if you remember, was once even the Prime Minister of his country. In one of his poems, full of social meaning, which my parents published in the Lit-Front, he says: ". . . Where are you going, Hassan, undocumented?" It seems to me that our case is quite the same! Where are you going, Master Bruegel, undocumented?

Despite all that, Flemish scholars believe that the great painter, whom they did not want to share in any way with the Dutch, was theirs, if he worked on their territory and was born "somewhere in the Netherlands" between 1525 and 1530, and died on September 5, 1569 in Brussels. At best, he is only 44 years old. So what? Mozart lived even less. And yet, he too is a genius. It's not a matter of age, it's a matter of talent. The talent my favourite, obviously, had. In abundance. It fills every corner of his small and large, oil or graphic works. Is the image painted in “The Artist and the Connoisseur”, which is housed in the Albertina Museum in Vienna, his self-portrait? Imagine, not even that is established! Total fog! But since Bruegel himself is a bright sun, I hope that our descendants will clarify the details of which I have spoken to you so far. If, of course, we do not break and burn his paintings scattered throughout the various museums of our old continent, which has a special taste for war. From the ancient Achaeans until now, for your information, it has led more than a thousand! Damn, I digress again. But I will immediately return to the Pieter Bruegel topic. However, my dear, it is certainly known that the man of whom I can tell you neither where he was born nor where he was buried, studied painting at Anvers in the studio of the famous painter Cook van Alst, the head of the Anvers painters, whose daughter he later married. "Prosaic story!" you will say. Who knows, may be it was lyrical. Looking at his paintings, it seems to me that he was a sentimental and extremely sensitive nature. Otherwise, I'm sure, he wouldn't have painted what he painted. His contemporaries called him by two nicknames: "Bruegel the Funny" and "Bruegel the Peasant"! It is also known with certainty—this time on paper—that he was inscribed in the Guild of Painters "St. Luke" at Anvers in 1551—the Flemings would be infuriated if they heard that I continually called their Antwerp by its French name, in which he acquired the right to become independent. I am convinced that the acquisition of such a title in his time was a job much more difficult than to graduate from several universities today. I recently read an ancient Florentine regulation about the training and duties of apprentices who entered the Bottega of a full-fledged artist-master, and I am convinced that none of today's students in modern art academies could endure this "training". It includes everything from sweeping the floor and cooking in the master's kitchen to the preparation of paints, canvases or drawing boards, not counting the painting itself, which was allowed to the apprentice only after dozens of secondary tasks in the "backgrounds" of the paintings or in the painting of some minor detail. On top of what has been said so far, the blows on the neck naturally follow, because the people of that time were still deeply convinced that "The stick came out of heaven."

After completing his studies in Anvers, Master Bruegel headed to Italy to "finish his studies." But strange as it sounds, he was not influenced by the Italians one iota, although as a man of marked taste he could not help but admire their mastery. For him, of greater importance then turned out to be his very journey along the European roads, along which he walked as a real "sans-culotte" who he, actually, was. On his way home, like Dürer, he was most impressed by the dizzyingly beautiful passes and landscapes. Master Bruegel liked them so much that he did not tire of painting them until the end of his short life as landscape backgrounds of the majority of his paintings, not counting his graphics dedicated to them. Not less impression, on his return home, made on him the art of his country Hieronymus Bosch, and under his influence the Dutchman "redirected" his interests from landscape to satirical drawing and painting. After a relatively long stay in Anvers, where my favourite painted mainly for the art dealer and publisher Hieronymus Kok, owner of the small art gallery "The Meeting of the Four Winds", manifesting himself mainly as an author of small-format landscapes, Master Bruegel left Anvers and moved to rich Brussels.

There he took with him the memories of his native fallow lands, of the peasants, and of his life along the banks of the Scheldt, at whose mouth sailboats from all over the world arrived.

Meanwhile, his engravings, full of moralising plots related to the virtues and vices of man, spread by Kok throughout the Netherlands, had already made him quite popular with his compatriots, and he began to earn good money in Brussels. But this brilliant start of his career coincided with one of the worst periods in the history of his native "Low Land". In those years, the Netherlands was owned by the Habsburgs, i.e. it belonged to the domain of the Kaiser of the Holy Roman Germanic Empire, or more precisely, to King Charles V of Spain. One legend tells us that when Titian painted that same Kaiser Charles V, in one of the sessions he dropped his brush and "His Catholic Majesty" quickly got up from his seat and handed it to him. The kind act greatly embarrassed the otherwise arrogant in character Venetian, and he involuntarily said:

"But what are you doing, Your Majesty?" to which Charles V replied, "Nothing else, dear Titian, but that I pass the brush to a genius artist!"

Italians say of such stories: "If it is not true, at least it is well said!" Naturally, it is possible that there is a grain of truth in this anecdote but the rebellious Dutchmen remembered the same kind Kaiser as a cruel tyrant. During his reign, the once flourishing Netherlands was turned into a real slaughterhouse and brought to a beggar's stick. I don't know if you know, but when the Flemish city of Ghent rebelled, Charles V himself led his army during the siege, and after the surrender of Ghent he acted with his defenders as a true Assyrian ruler. He killed and burned at the stakes with the help of the Holy Inquisition more than two-thirds of its entire population! I believe that with this data you cannot imagine the "brilliant" beginning of Bruegel's career as a "free artist". But it seems that he was a man of sound nerves, and although he did not participate directly in the struggles of his people against the Spaniards, he fought against their yoke with all his art. Except, of course, his landscapes, where, I suppose, his lyrical soul found rest and peace. In order not to think that this is not the idle talk of a bored traveler in a hotel after ten o'clock in the evening, I strongly recommend that you get from your library an album of Bruegel's works and then you will see for yourself that I am right. Whether I'm right or wrong is not important. The majority of people who are engaged in art history and aesthetics, in general, are of the same opinion. But don’t let me influence you! In art, everyone has the right to see things in their own way. Otherwise, the Roman proverb "As many heads, so as many opinions" would be canceled. But it must not be thrown away! However, after this sociological micro-pause, let's go back to the picturesque "bosom" of Master Bruegel. And so, my dear Master, I have tried in the most conscientious and shortest possible way to paint for you the historical canvas on which the hero of my letter has left a mark. Listen to some more chronological details about his scenic "actions".

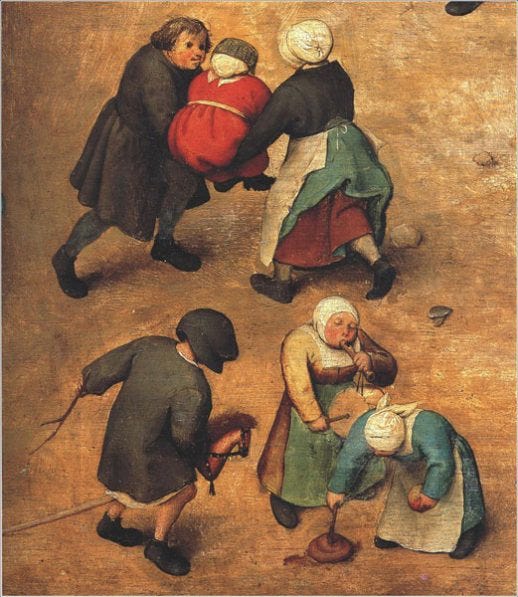

As a result, after his landscapes, appeared his first satirical paintings, scouring stupidity, gluttony, cruelty, injustice, and, in general, all the qualities peculiar of "Homo Sapiens" that distinguish him from "cattle," i.e., from animals. The awakened conscience of the man Bruegel helped the artist Bruegel to ridicule them in his famous multi-figure compositions in a magnificent way, using the high point of view, as the professionals say. Or, more figuratively explained: as if he was watching them from a slow-flying helicopter. Among this seemingly cheerful "panopticon" of satyrs is, for example, his famous painting "Flemish Proverbs"—a synthesis of sound humour and thin satire that, allied, spit like a scourge! Not less expressive than "Proverbs" is "The Fight between Carnival and Lent". His "Children's Games"—believe me—are a hymn to the carelessness and joy of children of all times.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Detail from Children’s Play, 1560. Art History Museum, Vienna.

Of course, in addition to these three satirical paintings, Master Bruegel has created many other similar canvases and engravings. It doesn't make sense to list them to the last. But if you could look at them together, you would see in them that the great Dutch not only scourges vice, but also has a great social understanding of the reasons why this vice exists. He shows true love for underprivileged people. Isn't that the purest humanism?

If you turn now to the second plot cycle in Bruegel's work, where he is already painting the Dutch patriot and citizen of his suffering homeland, you will immediately see something quite different from what I just mentioned. In “The Massacre of Innocents”, located in Vienna, in Madrid's “Triumph of Death”, in “The Mad Greta” of the Darmstadt Museum, without even adding to them “The Magpie on the Gallows”, a painting from the last days of his life, you will feel Bruegel's intense hatred for violence and for those who cause it to exist. You won’t believe that the paintings of the cycle "Seasons", radiating such beauty and tranquility, were painted by his hand. All the paintings mentioned are sinister in sound, but the scariest of them seems to be the "Massacre the Innocents". The small Dutch village is shown surrounded by Spanish soldiers. No one can get out of their iron hoop. And although the plot of the painting is biblical, the reality shown in it is Dutch. It is emphasised in the clothes of the peasants, in the weapons and uniforms of the horsemen, in everything. In the left lower corner of that painting, you can see how a wretch managed to get out of the iron hoop and how a Spaniard-horseman overtakes her to kill her child. It is most reminiscent of the torment of a small people who groaned for a long time under the cruel yoke of the empire that ruled half the globe. I can't tell you how this picture came about or where it was first seen, but for me it is one of the scariest autobiographical pages about the mental anguish of Bruegel, who was also a slave like his countrymen and perpetuated these anguish through it.

I think I went too far. My letter got really long, Vladik, but I just can't stop. And now I'm going to open another page of Bruegel's existence—the contemplative lyricist who looks at man with respect and love. I will tell you a few words about his "rural" paintings: "Peasant Holiday" and "Peasant Wedding", where the small figurines from the satirical boards are missing, but the bodies and faces of the tireless workers of the eternal land, who nothing can break, are seen in close-up. These two of his paintings are beautiful!

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Peasant Wedding, 1567. Art History Museum, Vienna.

From them radiates simplicity and pure human joy. It steams from each bright individualised face, from each individual rough and clumsy figure, intertwined harmoniously in the overall composition. You no longer see generalised human types, but concrete, living people who are the bearers of the most nuanced moods and experiences.

It must have been sometime around 1565, when Bruegel received from some wealthy art dealer the order for the “Seasons” cycle. The history of this cycle, so full of serenity and creative human work, is quite tragic. First, after the paintings were ready, the merchant locked them in his warehouse and never showed them either at home or anywhere else. And even less did he allow Bruegel himself to touch them or even look at them! Today, this cycle is scattered in various museums around the world. I even think that "The Harvest" is in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and "The Return of the Herd" and the wonderful "Winter", or, as it is often called, "The Return of the Hunters", are in Vienna. The whole cycle is painted on wooden boards. The dimensions of the individual paintings are impressive: an average of 115 by 160 centimetres. From the whole series, I seem to like his "Winter" the most.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Return of the Hunters, 1565. Art History Museum, Vienna.

In this magnificent landscape of snow-white Dutch soil, it feels as if the soft charm of the quiet winter day blends with the figures of skating hunters, peasants and children. Perhaps, it was this ability of Bruegel to merge the image of man with the surrounding natural environment into a single whole that distinguished him from many of his contemporaries. It seems to me that it is also what provided him with one of the first places in the Northern Renaissance. But, of course, whether this is the case is a "question for a discussion"!

Taken as a whole, the work of Pieter Bruegel represents the conclusion of the first stage in the development of Dutch realistic painting, and later Rubens, Rembrandt and Frans Halle, but they are already "another rubric", another topic. I wrote you a much longer letter than I planned. And yet, my tongue itches to add one more thing, Vladik. My favorite was, probably. one of the most wonderful historians of his days. He was the first "tribune of the plebs" in Dutch painting and the only master of the brush of his time, who showed through his art to the Renaissance people the crude and clumsy, but always full of life-force powerful image of the peasant. Bruegel made of this image his banner, and this flag — without sounding very pathetic — became the foreman of his own immortality.

And so, I end with that! The old neighbourhood clock on the nearby tower counts three after midnight. I wrote for five hours. If this not a letter, what is it! Have a good night, and all the best!

Yours Dragan

P.S. I forgot to tell you that Bruegel had two sons who also became famous painters. The most severe ordeal before his death was when he himself burned many of his own drawings. What a dirty reward for a life full of toil and valor! But he did it again not for himself, but to save his own family from possible persecution. Such were the times. Even the Romans said, "Rebus, sic stantibus”*.

* Do not forget death (Latin).

* Things according to conditions (Latin).

Dear siberakh@wp.pl , Thank you for joining my art and history substack and thank you for liking the Bruegel story! Glad you are enjoying it! The book consists of 28 small stories about great artists. 23 are already translated and posted. 5 more to go. Thank you again! Best wishes, Bilyana Martinovsky